In 2013, the direct cost of corrosion was 3.1% of the 15.1 trillion in U.S. GDP, which in June 2013 is estimated to equal $500.7 billion. Corrosion is a an electrochemical process where the metal is oxidized by virtue of interaction with its environment, which results in the metal returning to its most stable oxidative state. This article will discuss those factors that influence corrosion, especially in regard to the use of coatings designed to protect the metal to which they’re applied. Accordingly, consideration of the fundamental factors that influence corrosion processes as it relates to the use of organic coatings will be considered herein.

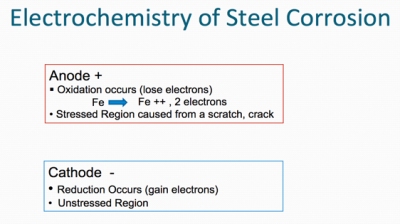

Metals desire to be in their most thermodynamically stable state, which, in simplified terms, is the naturally occurring state of matter in its lowest energy state. Metals ordinarily exist naturally as oxides (e.g. iron oxide, aluminum oxide, zinc oxide etc.), because oxides represent their lowest energy state. Oxidation occurs at the anode (positive electrode) and reduction occurs at the cathode (negative electrode). Corrosion is normally accelerated by the presence of water, oxygen, and salts (particularly of strong acids).

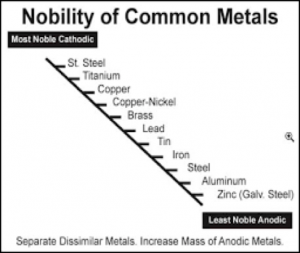

Figure I lists a series of metals and their ability to resist corrosion. The most common metals used in industry include steel (cold rolled and hot rolled steel), aluminum, galvanized steel (hot dip and electrogalvanized steel) as well as galvalume. The latter two metal substrates utilize either a zinc layer or an aluminum/zinc layer respectively on the surface of the steel to enhance corrosion resistance.

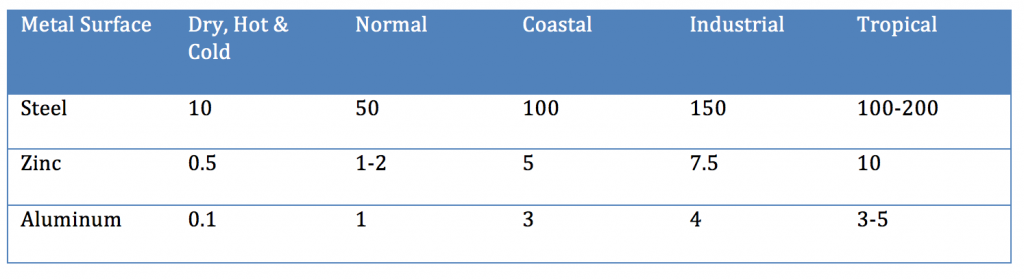

Even though aluminum and zinc are less noble than steel, when not coated with an organic coating, they provide longer-term improved corrosion resistance than steel. When steel rusts, the corrosion product (ferric oxide) is loosely attached to the surface, whereas in the case of aluminum or a zinc/aluminum alloy, the corrosion products form a more tightly knit adherent layer to the metal surface that decreases the subsequent rate of corrosion (Table III).

To read the rest of the article, head on over to Prospector to check it out!